DISCLAIMER: This English version is translated from the original French. In case of any discrepancy, the French version shall prevail.

| Author: | Bergeron, 1959 |

| Age: | Paleoproterozoic |

| Reference section: | None |

| Type area: | Ungava Peninsula (NTS sheets 35C, 35D, 35F, 35G and 35H) |

| Geological province: | Churchill Province |

| Geological subdivision: | Ungava Orogen / Southern Domain |

| Lithology: | Basaltic and komatiitic volcanic rocks |

| Type: | Lithostratigraphic |

| Rank: | Group |

| Status: | Formal |

| Use: | Active |

None

Background

According to Lamothe (2007), the Chukotat Group is a “[…] unit first mentioned by Bergeron (1959). Its lithological and lithogeochemical succession is described by Francis and Hynes (1979), Hynes and Francis (1982) and Francis et al. (1983). It was dated by Parrish (1989) and St-Onge et al. (1992).”

Recent geological mapping work carried out in this area has enabled Mathieu and Beaudette (2019) and Beaudette et al. (2020) to individualize informal units 6a and 6b, respectively.

Description

According to Lamothe (2007):

“Allochtonous volcanic unit located in the upper part of the South Domain. The Chukotat Group consists of komatiitic to tholeiitic mafic lava that forms a north-dipping homoclinal sequence with an apparent thickness of 7 km in its thinnest central section and 36 km in its western portion. The actual thickness of the unit varies, according to various estimates, between 2 km and 5 km (Hynes and Francis, 1982; Picard, 1989a; Moorhead, 1996a). The unit consists of interstratified underwater volcanic sequences with a MORB signature that generally evolve from olivine komatiitic basalts towards pyroxene tholeiitic basalts and finally towards plagioclase tholeiitic basalts (Hynes and Francis, 1982; Picard, 1989a). The unit’s lower contact overthrusts the Povungnituk [Group] and shows weak shearing (Lamothe et al., 1984; Moorhead, 1986; Budkewitsch, 1986; St-Onge et al., 1987).”

The importance of the shear zone between the Chukotat and Povungnituk groups was studied more recently by Bleeker and Kamo (2018) in the Raglan Mine area. They interpret the contact between the two groups as stratigraphic. A brecciated layer with fragments of the Povungnituk Group, hosted by Chukotat basalts, near the lower contact with the top of the Povungnituk Group, also suggests a stratigraphic relationship between the two groups (Moorhead, 1989).

Lamothe (2007) continued:

“Between the eastern end of the group to the western end of Chukotat Lake, the northern edge of the group exhibits intense penetrating deformation along the Bergeron Fault, which marks the beginning of the North Domain accretion zone and overthrusting of the Watts, Parent and Spartan groups on the Chukotat (Moorhead, 1989, 1996a). The interpretation proposed here differs from that of St-Onge et al. (2002) who extend the Bergeron Fault’s trace to Hudson Bay, approximately 20 km SW of the Pecten Harbour Pluton, thereby assigning all volcanics north of the fault to the Parent Group. From a petrographic and lithogeochemical perspective, these rocks have a signature identical to that of Chukotat plagioclase basalts, to which they are assigned in this compilation. For these reasons, Lamothe (this publication) instead curves the Bergeron Fault to the NW under Watts mafic and ultramafic slices. In addition to fault-edge zones, Chukotat rocks are very weakly deformed in the central and western parts of the orogen and moderately to highly deformed in the northern portion of the group between Carye Lake and Lanyan Lake. The presence of rare sedimentary and volcaniclastic beds locally accompanied by hematite alteration at the top of the Chukotat is mentioned by Roy (1989), Moorhead (1989) and Barrette (1990b).”

Following fieldwork in the summer of 2019, Beaudette et al. (2020) assigned the top sedimentary layers to the Hubert Formation, as they unconformably (angular discordance) overlie basalts.

Chukotat Group 1 (pPch1): Olivine Basalt

Olivine basalt is both the oldest member in the petrochemical evolution of Chukotat Group basalts (Francis and Hynes, 1979; Moorhead, 1989; Picard, 1989a, b) and the most widespread. The olivine basalt sequence consists mainly of pillowed flows and thin layers of massive flows. The rock is light green to buff-coloured in altered surface and grey-green in fresh exposure. Pillows are usually joint with small interstitial spaces filled with quartz and secondary carbonate (Togola, 1992), in addition to being very closely aligned (Moorhead, 1996). The pillows’ chilled margin contains 5% to 25% black olivine phenocrystals with microspinifex texture, while the core is generally phenocrystal-free. Massive flows vary in thickness from 2 m to 15 m. The alteration patina is reddish beige. Layered and differentiated massive flows were observed in the western part of the Korak Bay area (Togola, 1992).

In thin sections, samples display a matrix consisting of a very fine and partially crystallized lattice of acicular actinolite, sphene, epidote, chlorite and antigorite rods. Phenocrystals account for up to 30% of the mode and are 0.2 mm long. They mostly have an olivine habitus, more rarely pyroxene, and are totally replaced by an assemblage of antigorite and carbonates. Traces of fine euhedral epidote crystals develop in overprint, both in the matrix and phenocrystals.

Chukotat Group 2 (pPch2): Pyroxene Basalt

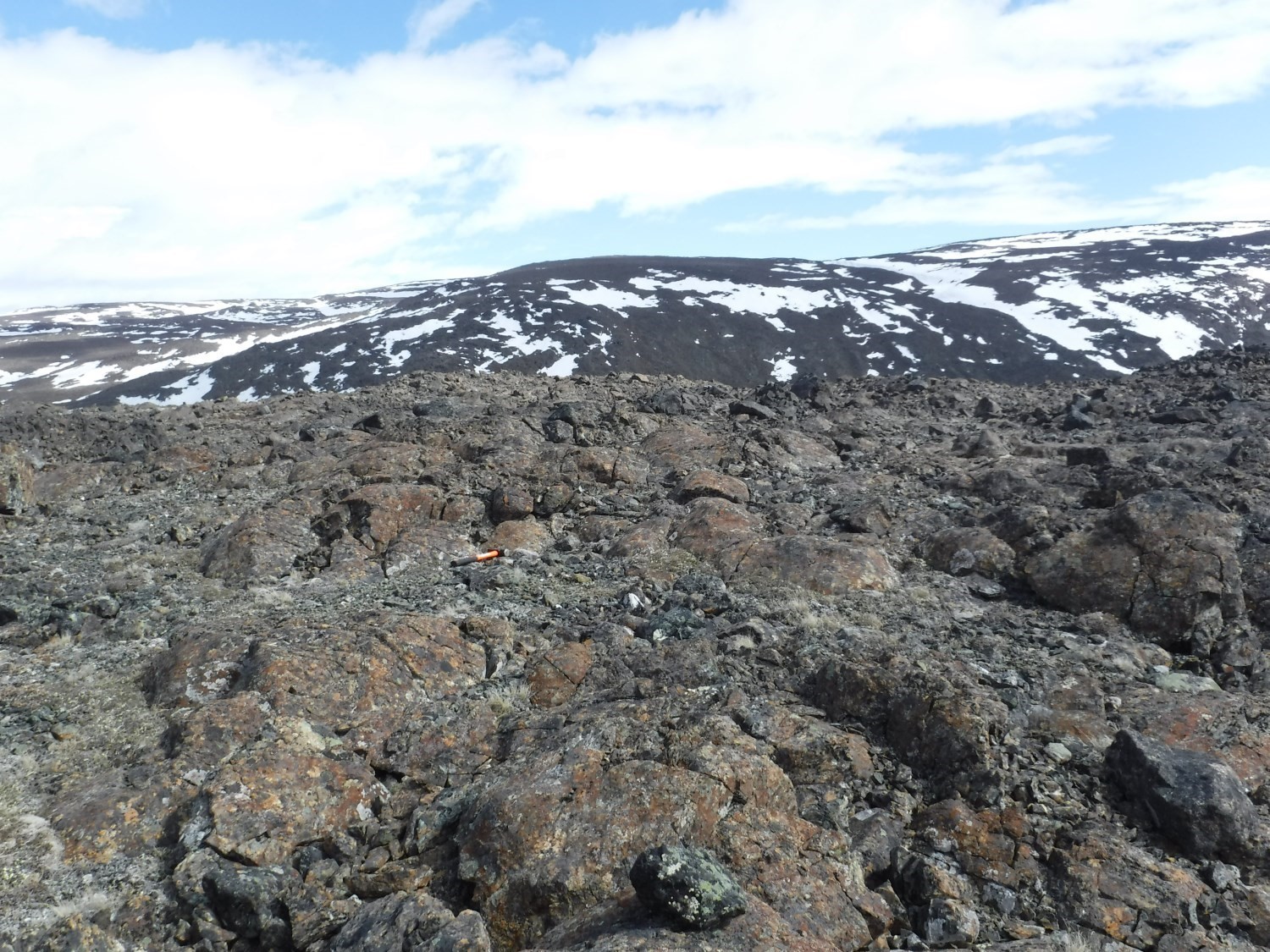

Pyroxene basalt is the intermediate unit in the petrochemical evolution of Chukotat basalts (Francis and Hynes, 1979; Moorhead, 1988; Picard, 1989a, b). Pyroxene basalt flows resemble olivine basalt flows; they differ by a reddish brown alteration patina and a microfractured texture giving a rubble appearance to several outcrops. The alteration colour is the result of their relatively higher iron content and, especially, their less magnesian character (Picard, 1986a, 1989b). Pillowed flows are slightly joint and quartz-carbonate interstitial spaces are larger than those of olivine basalt. Pillows are ovoid, multilobar and cross-connected. The most obvious feature of pyroxene basalt is the presence of whitish macrovarioles (1-8 mm in diameter) at pillow’s edges (Togola, 1992). This basalt is also characterized by the presence of <5% ferromagnesian phenocrystals (mostly pyroxene and sparse olivine) in the pillows’ chilled margin (Moorhead, 1996).

Chukotat Group 3 (pPch3): Pyroxene-Plagioclase Basalt

Pyroxene-plagioclase basalt, first known in the Vigneau area (Moorhead, 1988), has macroscopic characteristics intermediate between pyroxene basalt and plagioclase basalt. In fact, it has macroscopic criteria similar to plagioclase basalt (Picard, 1986a), but has the geochemical signature of pyroxene basalt (Picard, 1989b; Moorhead, 1996). The unit forms a large lens at the base of the Chukotat Group’s volcanic piling (Togola, 1992). This type of basalt is distinguished, among other things, by the absence of macrovarioles and the presence of microvarioles (1 mm in diameter) near the pillows’ chilled margins. In addition, ferromagnesian phenocrystals (absent to <2%) are contained in chilled margins (Togola, 1992). Pillows have very smooth surfaces and are less microfractured than those of pyroxene basalt; they are also light grey to very light green in fresh exposure.

Chukotat Group 4 (pPch4): Plagioclase Basalt

The final member of the petrochemical evolution of Chukotat basalts is plagioclase basalt of tholeiitic affinity (Francis and Hynes, 1979; Francis et al., 1981, 1983; Hynes and Francis, 1982; Picard, 1989a, b). This basalt forms the upper part of the Chukotat Group, but in places it is interstratified with olivine basalt and pyroxene basalt sequences. Massive flows are generally more abundant and relatively thicker (50-200 m) than the other two types of basalt (Togola, 1992). In addition, pillows are significantly smaller than olivine and pyroxene basalts. They generally have a more rounded shape, leaving many interstitial spaces filled with quartz and secondary calcite (Moorhead, 1996). In general, the pillow surface is very smooth and contrasts with the slightly fractured to very fractured appearance of olivine or pyroxene basalts. The chilled margin contains <5% (0-2% on average) ferromagnesian phenocrystals and 3 to 20% microlitic plagioclase recrystallized to epidote. In addition, plagioclase basalt is characterized by the presence of microvarioles (1 mm in diameter), elongated amygdules (1-5 mm in diameter) and bicoloured ground mass (purple to green) (Moorhead, 1996; Togola, 1992).

Macroscopic and microscopic petrographic observations made by Mathieu and Beaudette (2019) in the vicinity of the Bergeron Fault, in the eastern area, reveal a characteristic light orange-brown patina and a light green fresh surface. Basalt is aphanitic to fine grained and not magnetic. It commonly shows diffuse alteration to interstitial carbonate as well as veinlets overprinted by the last phase of deformation. The matrix consists of a fine-grained assemblage of green chlorite (2-40%), actinolite (0-60%) epidote (zoisite and pistachite; 2-40%) in partial or total replacement of plagioclase, interstitial carbonate (≤10%), sphene (2-20%) and plagioclase (5-40%), which gives a granoblastic texture to the rock. Relics of plagioclase phenocrystals (≤5%) completely replaced by epidote are observed in some samples. Accessory phases are opaque minerals (trace-5%), pyrite (0-3%), scapolite (trace), and hematite (trace). In the vicinity of the Bergeron Fault, all mineral phases define deformation, and carbonate (and to a lesser extent quartz) clusters and veinlets are commonly observed.

Chukotat Group 5 (pPch5): Mudrock, Volcaniclastics

Chukotat Group volcaniclastics include lapilli, crystal and block tuffs and volcanic breccias (Moorhead, 1989). Volcanic breccias are very small in the Chukotat volcanic piling (Togola, 1992). They are mainly found in pyroxene basalt and pyroxene-plagioclase basalt sequences. Several of these layers, usually 1 m thick, correspond to brecciated basalt flow tops. Fragments of these brecciated flows are very angular (1 cm to 1 m in diameter) and all come from massive or pillowed pyroxene and pyroxene-plagioclase basalt flows.

Chukotat Group 6 (pPch6): Altered Basalt

Chukotat Group 6a (pPch6a): Dolomitized Basalt

This informal unit was introduced by Mathieu and Beaudette (2019) to individualize highly altered basaltic flows, mapped in the vicinity of the Bergeron Fault and initially recognized by Gélinas (1952). Field descriptions indicate a dolomitic unit with a light brown patina and a brown sugar-coloured fresh surface, not magnetic and in diffuse contact with plagioclase pillow basalt (pPch4). The rock is foliated, locally banded, and alteration completely obliterates primary textures. Petrographic observations show a very fine-grained assemblage composed of the following phases: carbonate (20-80%), epidote-plagioclase (5-20%; giving a granoblastic texture to the rock), chlorite-actinolite (trace-55%), and opaque minerals (trace-10%). Secondary phases, not overprinted by foliation, are locally represented by medium-grained phenocrystals of carbonate and talc flakes (trace-15%).

Chukotat Group 6b (pPch6b): Hematitized, chloritized and Epidotized Basalt

This unit was introduced by Beaudette et al. (2020) in sheets 35G06 and 35G11 to individualize layers of altered pillow basalt located immediately south of the Bergeron Fault, already recognized by Giovenazzo (1989). These layers have been subjected to pervasive and veinlet alteration in hematite, epidote and chlorite giving the rocks a red and pale green patina with fir green and red veining. Primary volcanic textures have been preserved. Veinlets display centripetal zonation in hematite, carbonate and chlorite. The volcanic matrix is composed of acicular actinolite zones associated with variable amounts of epidote, sphene and chlorite, delimited by sphene, opaque minerals and epidote borders. Pervasive alteration results in a variation of the amount of hematite, epidote and chlorite within the matrix.

Thickness and Distribution

The Chukotat Group outcrops along the entire length of the Cape Smith Belt, i.e. over >350 km. It is oriented SW-NE in the western section, WSW-ENE in the central section and WNW-ESE in the eastern section.

Olivine basalt unit pPch1 is the most widespread of the group. Olivine basalt flows are 5 m to 25 m thick. Basalt forms three-dimensional pillows 1 m to 2 m in diameter and massive flows with prismatic joints. The contact with other basalts is visible, but its location is not specific as the transition is gradual. Pillow margins of unit pPch2 are variolitic: varioles are 5 mm to 15 mm in diameter and coalesce between 2 cm and 10 cm from the margin (Moorhead, 1989). Plagioclase basalt (unit pPch4) is less abundant than the first two units and is much smaller in the eastern section of the belt. On the other hand, it is the most important unit of the group in the western area, on the shores of Hudson Bay. It forms several massive or pillow layers further north of the sequence (Picard, 1989a).

As for volcanic rocks (pPch5), the volcanic breccia unit is thin (<1 m), whereas lapilli tuff is 5 m to 10 m thick (Moorhead, 1989). Carbonatized layers (pPch6a) do not exceed a few dozen metres thick and are interstratified with plagioclase basalt (pPch4), in the wall of the Bergeron Fault (Mathieu and Beaudette, 2019). Hematized, chloritized and epidotized basalt layers (pPch6b) are observed over >6 km long in the NW part of sheet 35G06, their apparent thickness varying from 50 m to 300 m. Unit pPch6 unit was observed immediately south of the Bergeron Fault, more specifically in sheets 35G09, 35G11, 35G12 and 35H12.

Dating

Chukotat Group basalts have not been dated. On the other hand, sills of the Lac Esker Suite are interpreted as feeder pipes of the latter. A gabbro sill intruding into sedimentary rocks of the Nuvilic Formation was dated 1918 +9/-7 Ma by Parrish (1989). This sample was reanalyzed by Bleeker and Kamo (2018) who obtained an age of 1881.5 ±0.9 Ma. Another sill, also in the Nuvilik Formation, was dated 1882.1 ±2.0 Ma (Bleeker and Kamo, 2018). Two gabbro sills intruding into Chukotat basalts were dated 1870 ±4 Ma (St-Onge et al., 1992) and 1883.0 ±1.7 Ma (Bleeker and Kamo, 2018). Basalts of the Chukotat Group are thus part of the emplacement of the Circum-Superior LIP, between 1880 Ma and 1870 Ma, 150 Ma after opening of the rift, along with the Labrador Trough’s second volcanic cycle (Ciborowski et al., 2017; Minifie et al., 2013; Mungall, 2007).

Stratigraphic Relationship(s)

According to Lamothe (2007): “The Chukotat is structurally overthrusting the Povungnituk Group and is overthrusted to the north by the Watts, Parent and Spartan groups in its eastern part.”

Moorhead (1989) mentions the presence of a breccia layer with volcanic fragments typical of the Cécilia Formation between two olivine basalt flows of the Chukotat Group, suggesting a proximal stratigraphic relationship between the two units, possibly separated by a normal fault. The nature of contact between the Chukotat and Povingnituk groups was studied more recently by Bleeker and Kamo (2018) in the Raglan Mine area. They interpret the contact between the two groups as stratigraphic.

Lamothe (2007) notes that “according to several researchers (Francis and Hynes, 1979; Francis et al., 1981, 1983; Hynes and Francis, 1982; Picard et al., 1990), the Chukotat represents the transition between continental rift-type volcanism (Povungnituk Group) and oceanic-type volcanism. According to St-Onge et al. (1992), the Chukotat Group is a volcanic assemblage deposited or preserved within a thrust belt on a continental basement, resulting from deepening of the continental rift initiated in the Paleoproterozoic.”

Paleontology

Does not apply.

References

Publications Available Through Sigéom Examine

Bergeron, R. 1959. Rapport préliminaire sur la région des monts Povungnituk, Nouveau-Québec. MRN. RP 392, 11 pages and 1 plan.

GIOVENAZZO, D. 1989. Indices minéralisés du secteur central de la fosse de l’Ungava: régions du lac Bélanger, des lacs Nuvilic et du lac Cécilia. MRN. ET 87-09, 42 pages and 3 plans.

Lamothe, D. 2007. Lexique stratigraphique de l’Orogène de l’Ungava. MRNF. DV 2007-03, 66 pages an 1 plan.

MATHIEU, G., BEAUDETTE, M. 2019. Geology of the Watts Lake area, Northern Domain, Ungava Orogen, Nunavik, Quebec, Canada. MERN. BG 2019-04.

Moorhead, J. 1989. Géologie de la région du lac Chukotat (Fosse de l’Ungava). MRN. ET 87-10, 64 pages an 2 plans.

Moorhead, J. 1996. Géologie de la région du lac Hubert (Fosse de l’Ungava). MRN. ET 91-06, 121 pages an 4 plans.

Picard, C. 1989a. Lithochimie des roches volcaniques protérozoïques de la partie occidentale de la Fosse de l’Ungava (région au sud du lac Lanyan). MRN. ET 87-14, 81 pages an 1 plan.

Picard, C.1989b. Pétrologie et volcanologie des roches volcaniques protérozoïques de la partie centrale de la Fosse de l’Ungava. MRN. ET 87-07, 98 pages an 4 plans.

Togola, N. 1992. Géologie de la région de la baie Korak (Fosse de l’Ungava). MRN. ET 91-07, 47 pages and 3 plans.

Other Publications

Bleeker, W., Kamo, S.L., 2018. Extent, origin, and deposit-scale controls of the 1883 Ma Circum-Superior large igneous province, northern Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nunavut and Labrador; In Targeted Geoscience Initiative: 2017 report of activities, volume 2, (ed.) N. Rogers; Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 8373, pages 5-14. doi.org/10.4095/306592

Ciborowski, T.J.R., Minifie, M.J., Kerr, A.C., Ernst, R.E., Baragar, W.R.A., Millar, I.L., 2017. A mantle plume origin for the Palaeoproterozoic circum-superior large Igneous Province. Precambrian Research, volume 294, pages 189-213. doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2017.03.001

Francis, D.M., Hynes, A.J., 1979. Komatiite-derived tholeiites in the Proterozoic of New Quebec. Earth and Planetary Science Letters; volume 44, pages 473-481. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(79)90085-2

Francis, D.M., Hynes, A.J., Ludden, J.N., Bédard, J., 1981. Crystal fractionation and partial melting in the petrogenesis of a Proterozoic high-MgO volcanic suite, Ungava, Québec. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology; volume 78, pages 27-36. Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/BF00371141

Hynes, A., Francis, D.M., 1982. A transect of the early Proterozoic Cape Smith foldbelt, New Quebec. Tectonophysics; volume 88, pages 23-59. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(82)90202-5.

Minifie, M.J., Kerr, C.K., Ernst, R.E., Hastie, A.R., Ciborowski, T.J.R., Desharnais, G.,Millar, I.L., 2013. The northern and southern sections of the western ca. 1880 Ma Circum-Superior large Igneous Province, North America: the Pickle Crow dyke connection? Lithos, volume 174, pages 217-235.

Mungall, J.E., 2007. Crustal contamination of picritic magmas during transport through dikes: the expo intrusive suite, Cape Smith Fold Belt, New Quebec. Journal of Petrolgy, volume 48, pages 1021-1039. doi:10.1093/petrology/egm009

Parrish, R.R., 1989. U-Pb geochronology of the Cape Smith Belt and Sugluk block, northern Quebec. Geoscience Canada; volume 16, pages 126-130. journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/GC/article/view/3609

Picard, C., Lamothe, D., Piboule, M., Oliver, R., 1990. Magmatic and geotectonic evolution of a Proterozoic oceanic basin system: the Cape Smith Thrust-Fold Belt (New-Quebec). Precambrian Research; volume 47, pages 223-249. doi:10.1016/0301-9268(90)90040-W

St-Onge, M.R., Lucas, S.B., Parrish, R.R., 1992. Terrane accretion in the internal zone of the Ungava orogen, northern Quebec. Part 1: Tectonostratigraphic assemblages and their tectonic implications. Canadian Journal of Earth Science; volume 29, pages 746-764. doi.org/10.1139/e92-064

St-Onge, M.R., Lucas, S.B., Scott, D.J., Begin, N.J., Helmstaedt, H., Carmichael, D.M., 1988. Thin-skinned imbrication and subsequent thick-skinned folding of rift-fill, transitional-crust, and ophiolite suites in the 1.9 Ga Cape Smith Belt, northern Quebec. Geological Survey of Canada, Paper No. 88-1C, pages 1-18. doi.org/10.4095/122611

Suggested Citation

Ministère de l’Énergie et des Ressources naturelles (MERN). Chukotat Group. Quebec Stratigraphic Lexicon. https://gq.mines.gouv.qc.ca/lexique-stratigraphique/province-de-churchill/groupe-de-chukotat [accessed on Day Month Year].

Contributors

|

First publication |

Mélina Langevin, GIT, B.Sc.; Guillaume Mathieu, Eng., M.Sc. guillaume.mathieu@mern.gouv.qc.ca (redaction) Mehdi A. Guemache, P. Geo., Ph.D. (coordination); James Moorhead, P. Geo., M.Sc. (critical review); Simon Auclair, P. Geo., M.Sc. (editing); Céline Dupuis, P. Geo., Ph.D. (English version); André Tremblay and Nathalie Bouchard (HTML editing). |

|

Revision |

Guillaume Mathieu, Eng., M.Sc. guillaume.mathieu@mern.gouv.qc.ca; Carl Bilodeau, P. Geo., M.Sc. carl.bilodeau@mern.gouv.qc.ca (redaction) Mehdi A. Guemache, P. Geo., Ph.D. (coordination); James Moorhead, P. Geo., M.Sc. (critical review); Simon Auclair, P. Geo., M.Sc. (editing); Céline Dupuis, P. Geo., Ph.D. (English version); André Tremblay (HTML editing). |