Dernière modification :

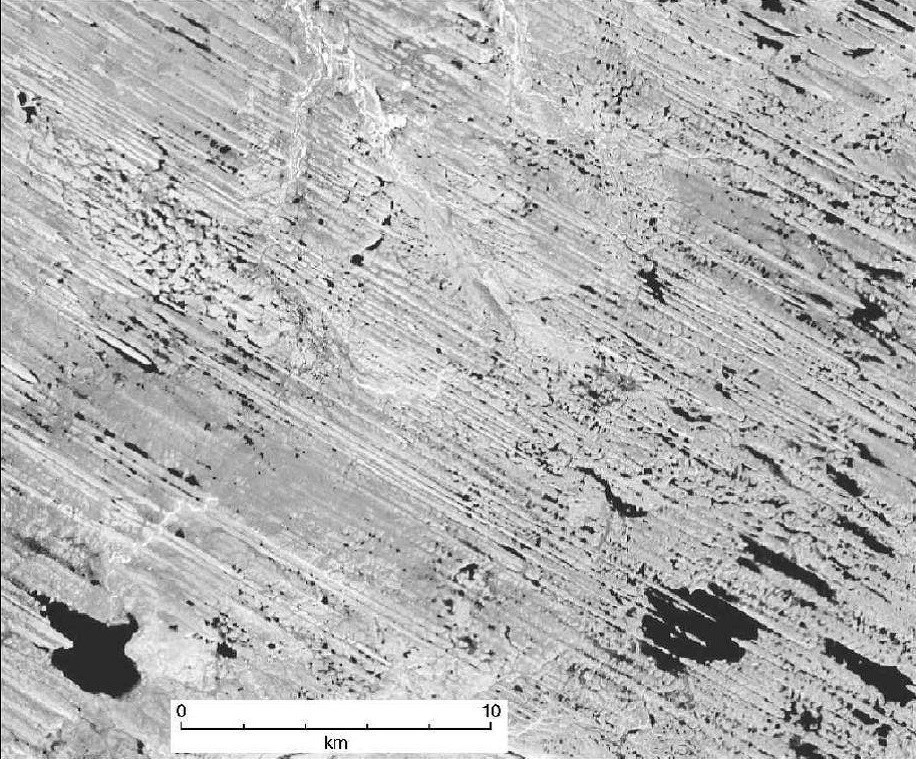

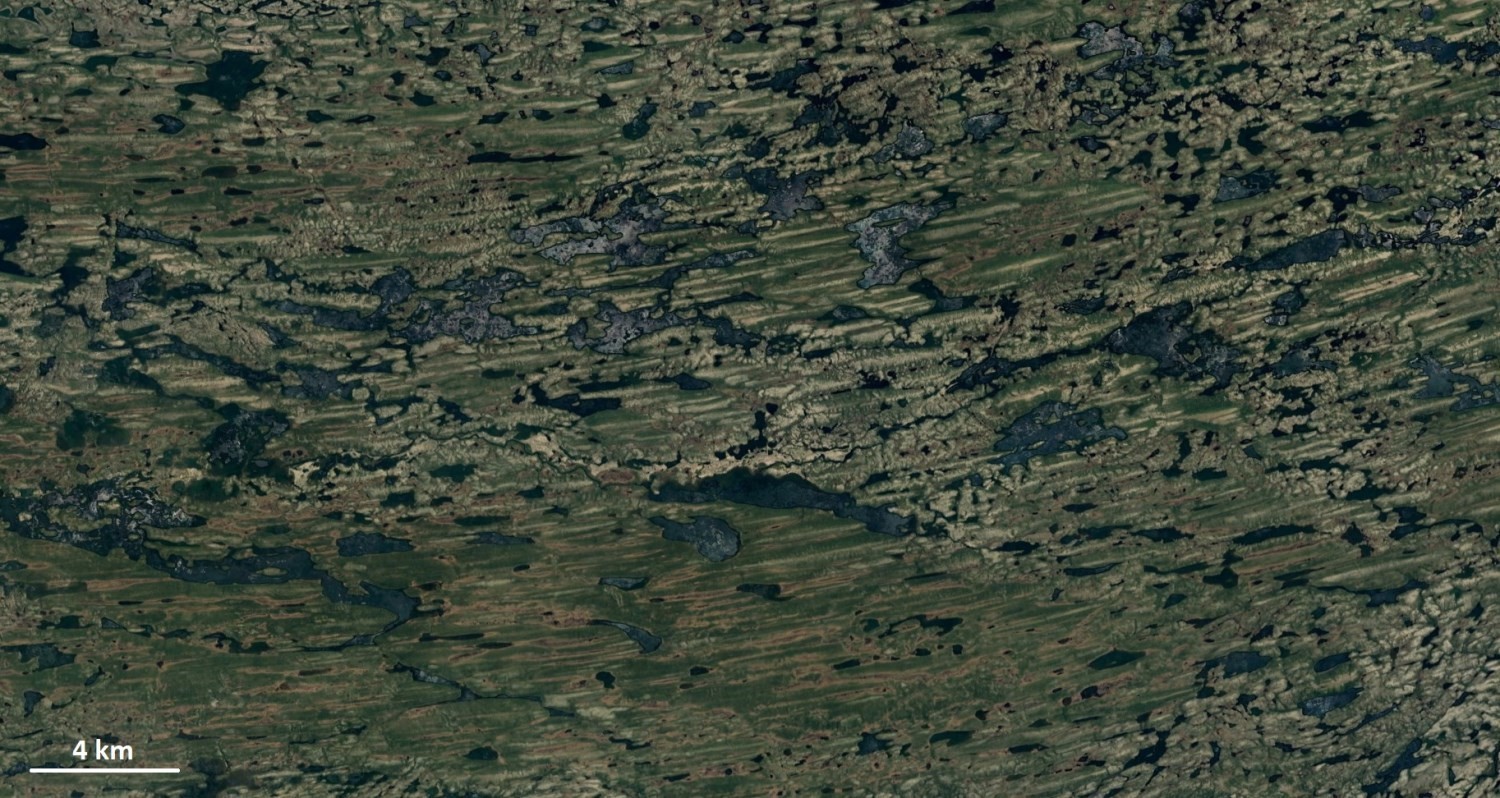

Les formes fuselées sont caractérisées par des crêtes allongées, rectilignes et de faible élévation, composées majoritairement de diamicton. Ce terme générique englobe plusieurs types de morphologies, dont les drumlins et les drumlinoïdes. Ils constituent probablement la morphologie glaciaire la plus étudiée au cours des dernières décennies. On dénombre plus de 1300 contributions (articles, résumés ou thèses) dans la littérature dont plus de 400 articles scientifiques publiés depuis 1980 (Menzies, 1984; Patterson et Hooke, 1995; Clark et al., 2009; Stokes et al., 2011; Spagnolo et al., 2012).

Étymologie

Le terme drumlin est dérivé du mot irlandais druim qui désigne « dos » ou « crête arrondie ». Ces formes furent reconnues sur les terrains englacés d’Irlande et nommées par Close (1866). L’appellation a ensuite été utilisée par différentes commissions géologiques ayant entrepris l’étude et la cartographie des formes glaciaires en Grande-Bretagne, en Irlande (Kinahan, 1874; Kilroe, 1888) et en Amérique du Nord (Davis, 1884; Upham, 1889; Tarr, 1894).

Le terme drumlinoïde est un terme apparenté à celui des drumlins , mais dont les critères morphologiques sont moins restrictifs.

Le terme drumlinoïde est un terme apparenté à celui des drumlins , mais dont les critères morphologiques sont moins restrictifs.

Dans la littérature anglophone, les termes fluted moraines, flutings ou streamed line ridges sont les meilleurs équivalents pour désigner les drumlinoïdes (Boulton, 1976; Rose, 1987; Benn et Evans, 2010). L’utilisation des différents termes ne fait pas l’objet de consensus et l’équivalent francophone de certains termes est nébuleux. Dans les publications du ministère, le terme drumlinoïde en est un de nature générale désignant les formes fuselées dont la taille est supérieure aux drumlins, regroupant ainsi toute forme fuselée (fluting) ou encore le terme anglophone de Mega-Scale Glacial Lineation (MSGL). Les drumlins à proprement parler font l’objet d’une désignation distincte (DU) dans la légende du Quaternaire, de même que les rainures glaciaires (flutes; RGL).

Description

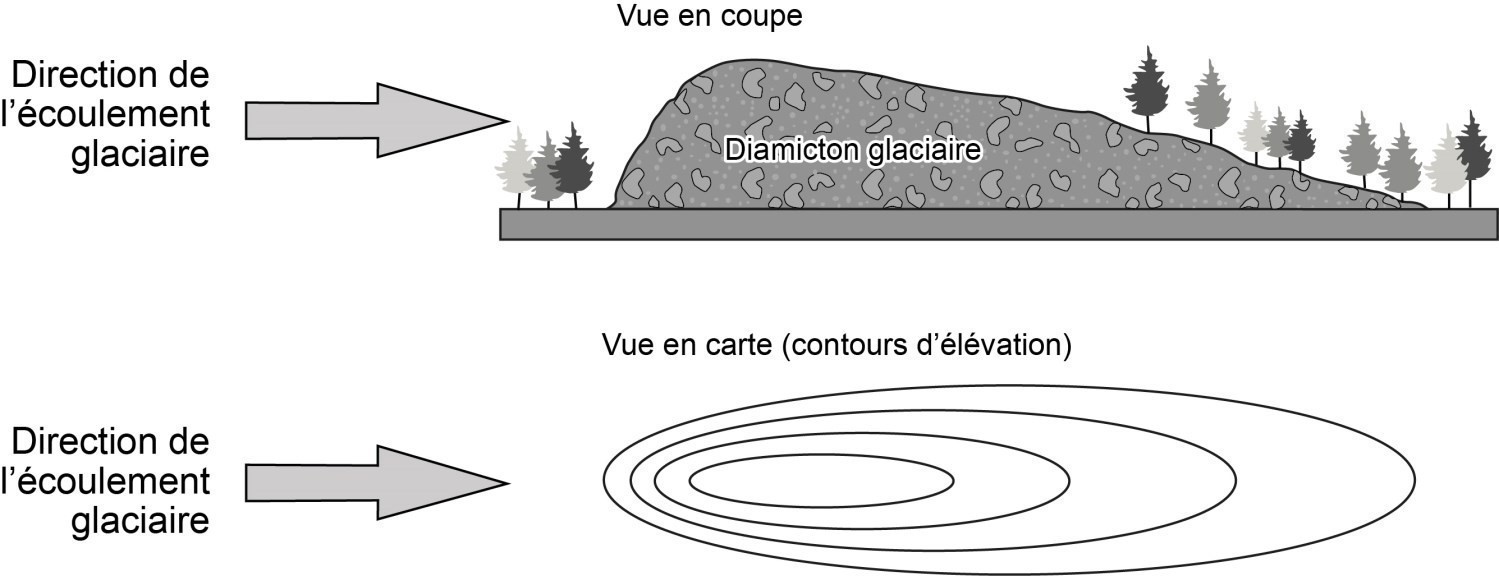

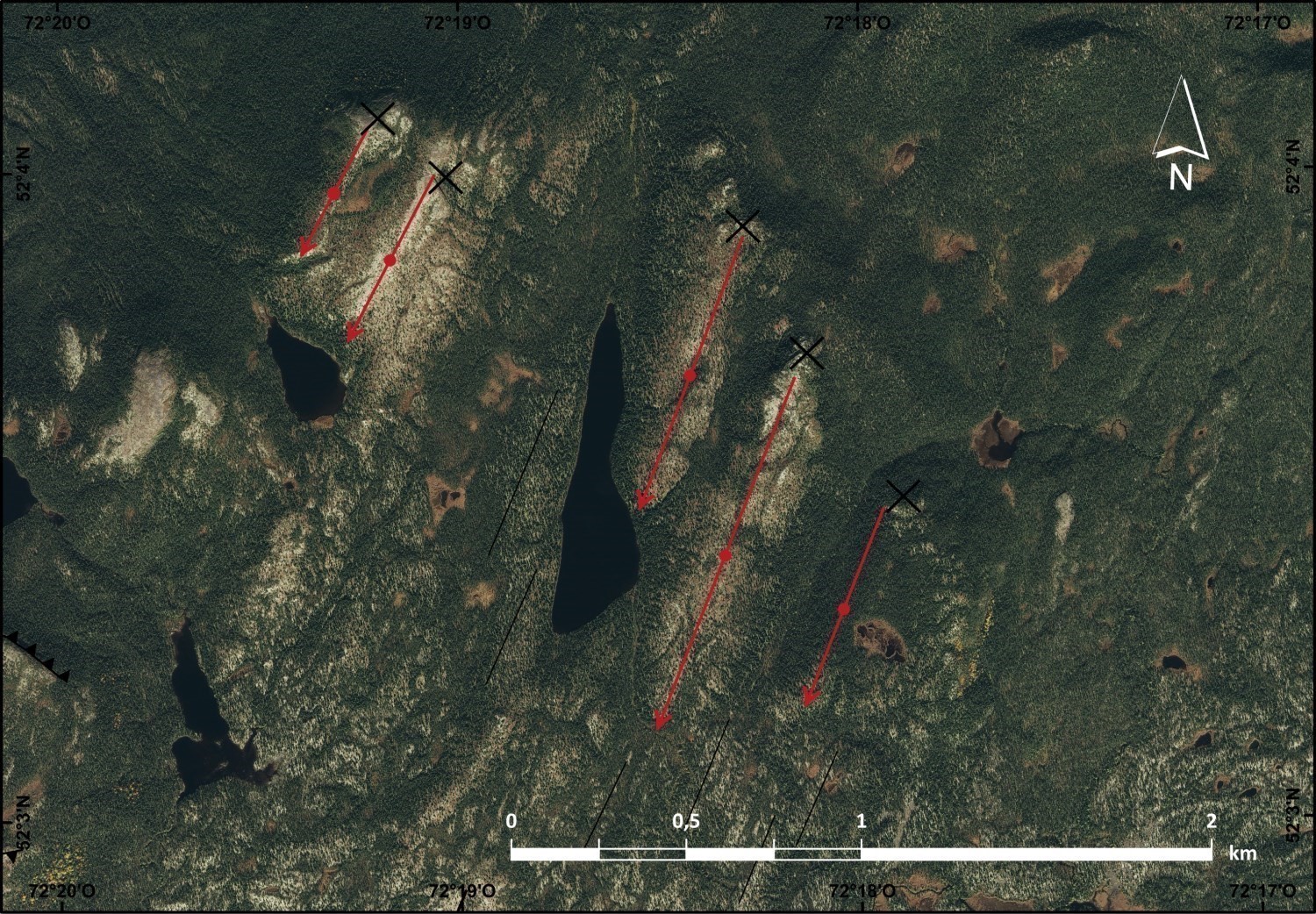

Un drumlin est une petite butte de forme ellipsoïdale et asymétrique caractérisée par un côté apex arrondi et un versant profilé à pente douce. La tête émoussée constitue le point d’élévation le plus élevé et se situe à l’amont glaciaire de la forme alors que le côté profilé indique le sens de l’écoulement glaciaire (Benn et Evans, 2010).

Un drumlin est une petite butte de forme ellipsoïdale et asymétrique caractérisée par un côté apex arrondi et un versant profilé à pente douce. La tête émoussée constitue le point d’élévation le plus élevé et se situe à l’amont glaciaire de la forme alors que le côté profilé indique le sens de l’écoulement glaciaire (Benn et Evans, 2010).

De nombreuses études ont démontré que leur morphologie peut grandement varier (longueur, largeur, hauteur, espacement, symétrie, forme en mèche ou parabolique; Menzies, 1979; Coudé 1989; Mitchell, 1994; Smalley and Warburton, 1994; Benn et Evans, 2010). L’analyse de regroupements ou essaims comprenant des dizaines de milliers de drumlins en Grande-Bretagne ainsi qu’en Irlande ont mené Clark et al., (2009) à établir les paramètres morphométriques moyens (longueurs, largeurs et ratios d’élongation) respectivement à 629 m, 209 m et 2,9. En général, les drumlins ont une longueur pouvant varier de 250 à 1000 m de long, 120 à 300 m de large et 0,5 à 40 m de hauteur (Clark et al., 2009; Spagnolo et al., 2012; Ely et al., 2018).

Le ratio d’élongation, déterminé par la longueur de la forme en fonction de sa largeur, se situe en général en dessous de 3. Au-dessus de ce seuil, les formes hectométriques à kilométriques seront généralement décrites comme des drumlinoïdes, et au-dessus de 10, comme des mega-scale glacial lineations (MSGL; voir étymologie; Stokes et Clark, 1999; 2002).

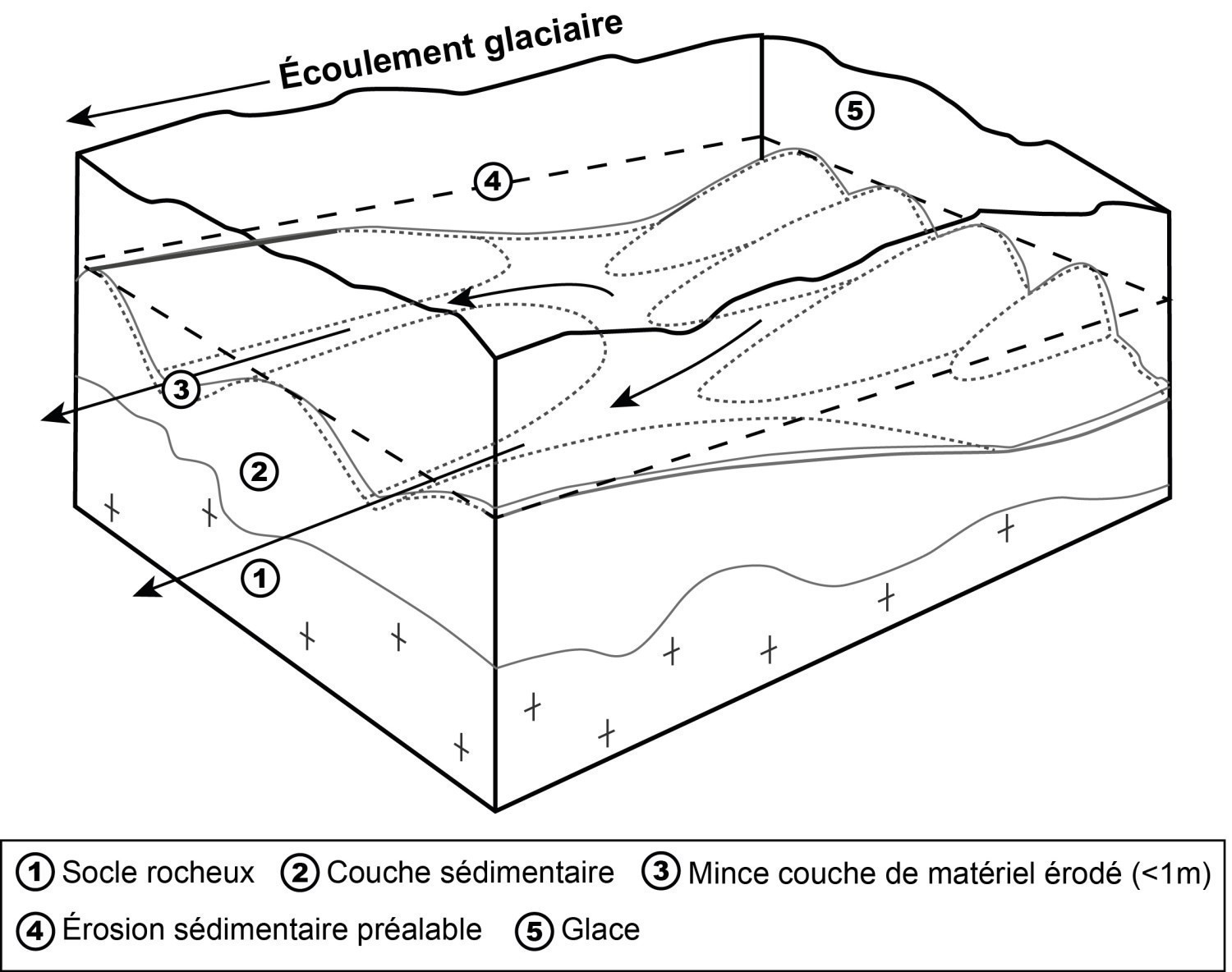

Plusieurs études ont démontré que la composition des drumlins peut varier grandement en fonction du substrat. Les drumlins sont majoritairement composés de sédiments glaciaires, bien que certaine spécimens ont un cœur rocheux (Menzies, 1979; Patterson et Hooke, 1995). La majorité des drumlins sont entièrement composés de diamicton glaciaire (Newman et Mickelson, 1994), mais peuvent également être composés d’un coeur de matériel trié avec une carapace de till en surface (Hart, 1994; 1995). Les caractéristiques sédimentaires des sédiments sous le till peuvent témoigner d’une mise en place antérieure (Krüger et Thomsen, 1984; Boulton 1987; Boyce et Eyles, 1991; Menzies et Brand, 2007; Benn et Evans, 2010) ou contemporaine à la formation des formes fuselées (Dardis et McCabe 1983; 1987; Dardis, 1985; McCabe et Dardis, 1989; Shaw, 1989; Benn et Evans, 2010; Evans et al., 2015). Certaines études font également mention de déformations glaciotectoniques dans les sédiments lors du processus de formation des drumlins (plis retournés, failles et structures d’échappements d’eau (Bluemle et Clayton, 1984; Stanford et Mickelson, 1985; Boulton et Hindmarsh, 1987; Hart, 1995; 1997; Stokes et al., 2011; Hermanowski et al., 2019).

Plusieurs études ont démontré que la composition des drumlins peut varier grandement en fonction du substrat. Les drumlins sont majoritairement composés de sédiments glaciaires, bien que certaine spécimens ont un cœur rocheux (Menzies, 1979; Patterson et Hooke, 1995). La majorité des drumlins sont entièrement composés de diamicton glaciaire (Newman et Mickelson, 1994), mais peuvent également être composés d’un coeur de matériel trié avec une carapace de till en surface (Hart, 1994; 1995). Les caractéristiques sédimentaires des sédiments sous le till peuvent témoigner d’une mise en place antérieure (Krüger et Thomsen, 1984; Boulton 1987; Boyce et Eyles, 1991; Menzies et Brand, 2007; Benn et Evans, 2010) ou contemporaine à la formation des formes fuselées (Dardis et McCabe 1983; 1987; Dardis, 1985; McCabe et Dardis, 1989; Shaw, 1989; Benn et Evans, 2010; Evans et al., 2015). Certaines études font également mention de déformations glaciotectoniques dans les sédiments lors du processus de formation des drumlins (plis retournés, failles et structures d’échappements d’eau (Bluemle et Clayton, 1984; Stanford et Mickelson, 1985; Boulton et Hindmarsh, 1987; Hart, 1995; 1997; Stokes et al., 2011; Hermanowski et al., 2019).

Les traînées morainiques derrière abri (crag & tail), se développent à l’aval d’un obstacle , communément un buton rocheux, et l’orientation de la traînées témoigne de la direction de l’écoulement glaciaire. Selon la légende adoptée par par Géologie Québec, ils sont cartographiés indépendamment des drumlins et drumlinoïdes (TMF).

Les traînées morainiques derrière abri (crag & tail), se développent à l’aval d’un obstacle , communément un buton rocheux, et l’orientation de la traînées témoigne de la direction de l’écoulement glaciaire. Selon la légende adoptée par par Géologie Québec, ils sont cartographiés indépendamment des drumlins et drumlinoïdes (TMF).

Genèse

Depuis quelques décennies, de nombreuses hypothèses, idées ou modèles conceptuels furent proposés sur le mécanisme de formation des drumlins sans qu’il n’y ait toutefois un consensus clair au sein de la communauté scientifique (Hall, 1815; Davis, 1884; Boulton, 1976; Menzies, 1979; 1987; Rose, 1987; Shaw, 2002; Stokes et al., 2013). Le débat sur l’origine des drumlins est encore d’actualité et parfois même controversé (Schomaker et al., 2018). Les principaux modèles suggérés dans les nombreuses études sont la formation de drumlins par des processus d’érosion, de déposition, ou par la théorie d’instabilité du milieu.

Le modèle érosionel s’explique par l’érosion différentielle du haut ves le bas à la semelle du glacier de matériel diamictique, fluvioglaciaire ou rocheux préexistant, et menant à l’individualisation de drumlins (Menzies, 1979; Boulton, 1987; Hart et Boulton, 1991; Hart, 1995; 1997; Knight; 2010; Eyles et al., 2016). Une branche de ce modèle, l’hypothèse de crues catastrophiques sous-glaciaires comme étant à l’origine de la formation des drumlins (Shaw, 1983; 1989; 1996; 2002; 2007; Shaw et al., 1989; Shoemaker, 1992; Rains et al., 1993), est contestée depuis son inception dans les années 1980 (Kehew et al., 1990; Forsström et Shaw, 1990; Clarke et al., 2004; 2005; Sharpe et al., 2005; Evans et al., 2006; Benn et al., 2007; Evans; 2010; Ó Cofaigh et al., 2010; Shaw, 2010a; 2010b; Shaw et Young 2010).

Le modèle érosionel s’explique par l’érosion différentielle du haut ves le bas à la semelle du glacier de matériel diamictique, fluvioglaciaire ou rocheux préexistant, et menant à l’individualisation de drumlins (Menzies, 1979; Boulton, 1987; Hart et Boulton, 1991; Hart, 1995; 1997; Knight; 2010; Eyles et al., 2016). Une branche de ce modèle, l’hypothèse de crues catastrophiques sous-glaciaires comme étant à l’origine de la formation des drumlins (Shaw, 1983; 1989; 1996; 2002; 2007; Shaw et al., 1989; Shoemaker, 1992; Rains et al., 1993), est contestée depuis son inception dans les années 1980 (Kehew et al., 1990; Forsström et Shaw, 1990; Clarke et al., 2004; 2005; Sharpe et al., 2005; Evans et al., 2006; Benn et al., 2007; Evans; 2010; Ó Cofaigh et al., 2010; Shaw, 2010a; 2010b; Shaw et Young 2010).

Les drumlins pourraient également se former par déposition de sédiments meubles à l’aval d’un obstacle (buton rocheux, till consolidé, sédiments compétents; Fairchild, 1929; Boulton, 1987; Menzies et al., 2016), ou par accrétion continuelle de sédiments à la queue de la forme fuselée (Dardis et McCabe, 1983; Dardis et al., 1984; Hart et Boulton, 1991; Dardis et Hanvey, 1994; Patterson et Hooke, 1995; Fowler , 2009; Knight, 2010; Barchyn et al., 2016; Hart et al., 2018). Contrairement au modèle érosionel, la construction des drumlins se ferait dans ce cas-ci par accrétion verticale et donc de « bas en haut » (Eyles et al., 2016).

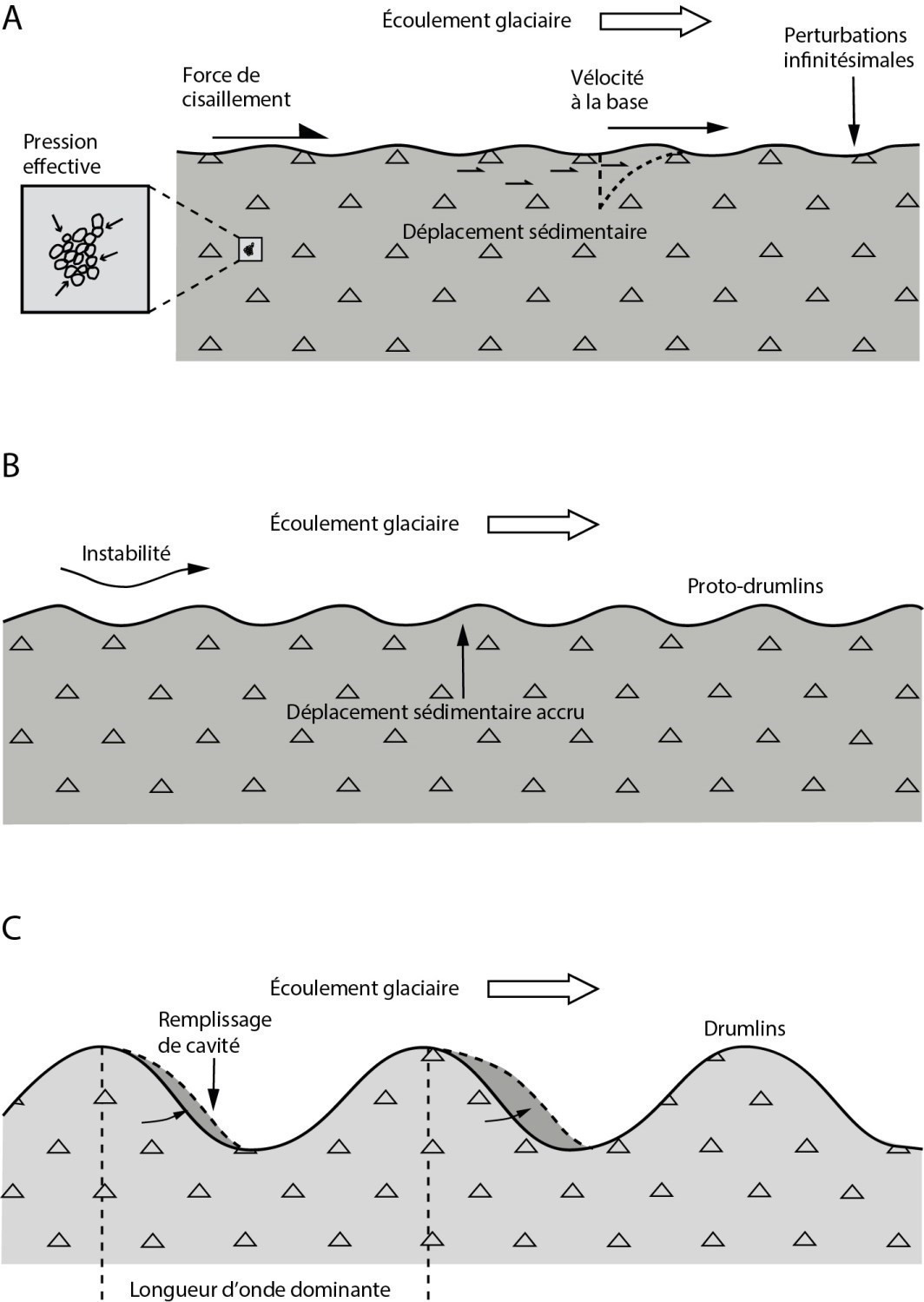

La théorie de l’instabilité du milieu pour expliquer la formation des drumlins et autres formes sous-glaciaires fut introduite durant les années 1990 (Patterson et Hooke, 1995; Hindmarsh 1996; 1998; 1999; Fowler, 2000; 2009; Schoof, 2007; Dunlop et al., 2008; Clark et al., 2009; 2018; Clark, 2010; Stokes et al., 2011; 2013; Spagnolo et al., 2012; Fowler et al., 2013; Hillier et al., 2013; 2018; Eyles et al., 2016). Cette théorie prédit que des légères variations de relief local (instabilité) sont suffisantes pour induire une boucle de rétroaction positive dans les processus d’érosion et de déposition. Par l’entremise de cette boucle, l’instabilité du milieu augmente de façon exponentielle jusqu’à l’obtention d’une longueur d’onde précise où il y a formation d’une multitude de formes ayant une morphologie et un espacement similaire. Ce mécanisme est couramment observé dans l’organisation des sédiments éoliens et fluviaux, comme par exemple pour les ondulations répétitives de rides de courant sur une plage sableuse. En contexte sous-glaciaire, la variation des conditions basales de la glace génère une instabilité rhéologique assez importante pour qu’il y ait déformation du substrat diamictique saturé en eau et la formation subséquente de formes sous-glaciaires, notamment de formes fuselées.

La théorie de l’instabilité du milieu pour expliquer la formation des drumlins et autres formes sous-glaciaires fut introduite durant les années 1990 (Patterson et Hooke, 1995; Hindmarsh 1996; 1998; 1999; Fowler, 2000; 2009; Schoof, 2007; Dunlop et al., 2008; Clark et al., 2009; 2018; Clark, 2010; Stokes et al., 2011; 2013; Spagnolo et al., 2012; Fowler et al., 2013; Hillier et al., 2013; 2018; Eyles et al., 2016). Cette théorie prédit que des légères variations de relief local (instabilité) sont suffisantes pour induire une boucle de rétroaction positive dans les processus d’érosion et de déposition. Par l’entremise de cette boucle, l’instabilité du milieu augmente de façon exponentielle jusqu’à l’obtention d’une longueur d’onde précise où il y a formation d’une multitude de formes ayant une morphologie et un espacement similaire. Ce mécanisme est couramment observé dans l’organisation des sédiments éoliens et fluviaux, comme par exemple pour les ondulations répétitives de rides de courant sur une plage sableuse. En contexte sous-glaciaire, la variation des conditions basales de la glace génère une instabilité rhéologique assez importante pour qu’il y ait déformation du substrat diamictique saturé en eau et la formation subséquente de formes sous-glaciaires, notamment de formes fuselées.

Répartition spatiale

Les drumlins sont une forme ubiquiste présente dans la majorité des régions ayant été englacées au cours du dernier épisode glaciaire (Flint, 1971; Embleton et King, 1975; Menzies, 1979; 1984; Clark et al., 2009). Ils sont souvent regroupés en champs dont les populations peuvent représenter plusieurs milliers de spécimens (Benn et Evans, 2010). En Amérique du Nord, les essaims les plus importants de drumlins se situent à New York (10 000), en Nouvelle-Angleterre (3000), au Wisconsin (5000) et en Nouvelle-Écosse (2300; Menzies, 1979).

Les drumlins sont une forme ubiquiste présente dans la majorité des régions ayant été englacées au cours du dernier épisode glaciaire (Flint, 1971; Embleton et King, 1975; Menzies, 1979; 1984; Clark et al., 2009). Ils sont souvent regroupés en champs dont les populations peuvent représenter plusieurs milliers de spécimens (Benn et Evans, 2010). En Amérique du Nord, les essaims les plus importants de drumlins se situent à New York (10 000), en Nouvelle-Angleterre (3000), au Wisconsin (5000) et en Nouvelle-Écosse (2300; Menzies, 1979).

Les champs de formes fuselées sont généralement formés dans les zones dépressionnaires, à l’occurrence dans les basses-terres et les vallées, où le stress basal sous-glaciaire est peu élevé, la pression d’eau interstitielle est forte et la présence de sédiments est importante (Mitchell, 1994; Kovanen et Slaymaker, 2004; Mitchell et Riley, 2006). Toutefois, les formes fuselées ne sont pas uniquement confinées dans les dépressions topographiques. En effet, leur présence a également été décrite sur certains plateaux soulignant une mise en place indépendante d’un contrôle topographique (Patterson et Hooke, 1995). De plus, contrairement à ce qui fut suggéré auparavant (Smalley et Unwin, 1968; Francek, 1991), les études récentes tendent à démontrer que la distribution des drumlins est rarement aléatoire à l’intérieur des champs et leur mise en place se ferait selon un espacement régulier pouvant varier entre 100 à 1200 m (Fowler, 2000; Clark, 2010; Clark et al., 2018). Finalement, la nature et les propriétés du substrat jouent aussi un rôle dans leur distribution (Menzies, 1979; Boulton, 1987; Patterson et Hooke, 1995).

De par l’uniformité de leurs caractéristisques à l’intérieur d’un même champs (orientation analogue, proximité et pluralité des formes, morphologies similaires, etc.), les regroupements de formes fuselées servent généralement à définir des patrons d’écoulement régionaux (flow-set; Clark, 1994; 1999; Clark et al., 2000). Ces champs ont tendance à se former à proximité (~80 km) de la marge glaciaire (Patterson et Hooke, 1995) et l’étude de leur distribution est essentielle à la compréhension ainsi qu’à la reconstruction de la dynamique des anciennes calottes glaciaires (Clark et al., 2000).

Références

Autres publications

BARCHYN, T.E. – DOWLING, T.P.F. – STOKES, C.R. – HUGENHOLTZ, C.H., 2016 – Subglacial bed form morphology controlled by ice speed and sediment thickness. Geophysical Research Letters; volume 43, pages 7572–7580. doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069558

BENN, D.I. – EVANS, D.J.A., 2010 – Glaciers and glaciations, second edition. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London and New York, 802 pages. doi.org/10.4324/9780203785010

BENN, D.I. – EVANS, D.J.A. – SHAW, J. – MUNRO-STASIUK, M., 2007 – Subglacial Megafloods: Outrageous Hypothesis or Just Outrageous? Dans: Glacier Science and Environmental Change, John Wiley & Sons, pages 42–50. doi.org/10.1002/9780470750636.ch8

BLUEMLE, J.P. – CLAYTON, L., 1984 – Large‐scale glacial thrusting and related processes in North Dakota. Boreas; volume 13, pages 279–299. doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3885.1984.tb01124.x

BOULTON, G.S., 1976 – The origin of glacially fluted surfaces-observations and theory. Journal of Glaciology; volume 17, pages 287–309. doi.org/10.3189/S0022143000013605

BOULTON, G.S., 1987 – A theory of drumlin formation by subglacial sediment deformation. Dans : Menzies, J. et Rose, J. (eds), Drumlin Symposium 1987, Balkema, Rotterdam, pages 25–80.

BOULTON, G.S. – HINDMARSH, R.C.A., 1987 – Sediment deformation beneath glaciers: Rheology and geological consequences. Journal of Geophysical Research; volume 92, pages 9059–9082. doi.org/10.1029/JB092iB09p09059

BOYCE, J.I. – EYLES, N., 1991 – Drumlins carved by deforming till streams below the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Geology; volume 19, pages 787–790. doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<0787:DCBDTS>2.3.CO;2

CLARK, C.D., 1994 – Large-scale ice-moulding: a discussion of genesis and glaciological significance. Sedimentary Geology; volume 91, pages 253–268. doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(94)90133-3

CLARK, C.D., 1999 – Glaciodynamic context of subglacial bedform generation and preservation. Annals of Glaciology; volume 28, pages 23–32. doi.org/10.3189/172756499781821832

CLARK, C.D., 2010 – Emergent drumlins and their clones: From till dilatancy to flow instabilities. Journal of Glaciology; volume 56, pages 1011–1025. doi.org/10.3189/002214311796406068

CLARK, C.D. – ELY, J.C. – SPAGNOLO, M. – HAHN, U. – HUGHES, A.L.C. – STOKES, C.R., 2018 – Spatial organization of drumlins. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms; volume 43, pages 499–513. doi.org/10.1002/esp.4192

CLARK, C.D. – HUGHES, A.L.C. – GREENWOOD, S.L. – SPAGNOLO, M.S. – NG, F.S.L., 2009 – Size and shape characteristics of drumlins, derived from a large sample, and associated scaling laws. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 28, pages 677–692. doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.08.035

CLARK, C.D. – KNIGHT, J.K. – GRAY, J.T., 2000 – Geomorphological reconstruction of the Labrador Sector of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 19, pages 1343–1366. doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00098-0

CLARK, C.D. – TULACZYK, S.M. – STOKES, C.R. – CANALS, M., 2003 – A groove-ploughing theory for the production of mega-scale glacial lineations, and implications for ice-stream mechanics. Journal of Glaciology; volume 49, pages 240–256. doi.org/10.3189/172756503781830719

CLARKE, G.K.C. – LEVERINGTON, D.W. – TELLER, J.T. – DYKE, A.S., 2004 – Paleohydraulics of the last outburst flood from glacial Lake Agassiz and the 8200BP cold event. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 23, pages 389–407. doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.06.004

CLARKE, G.K.C. – LEVERINGTON, D.W. – TELLER, J.T. – DYKE, A.S. – MARSHALL, S.J., 2005 – Fresh arguments against the Shaw megaflood hypothesis. A reply to comments by David Sharpe on “Paleohydraulics of the last outburst flood from glacial Lake Agassiz and the 8200 BP cold event”. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 24, pages 1533–1541. doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.12.003

CLOSE, M.H., 1866 – Notes on the general glaciation of Ireland. Journal of the Geological Society of Ireland; volume 1, pages 207–242. Source

COUDÉ, A., 1989 – Comparative study of three drumlin fields in western Ireland: geomorphological data and genetic implications. Sedimentary Geology; volume 62, pages 321–335. doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(89)90122-X

DARDIS, G.F., 1985 – Till facies associations in drumlins and some implications for their mode of formation. Geografiska Annaler, Series A; volume 67A, pages 13–22. doi.org/10.1080/04353676.1985.11880126

DARDIS, G.F. – HANVEY, P.M., 1994 – Sedimentation in a drumlin lee-side subglacial wave cavity, northwest Ireland. Sedimentary Geology; volume 91, pages 97–114. doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(94)90124-4

DARDIS, G.F. – MCCABE, A.M., 1983 – Fades of subglacial channel sedimentation in late‐Pleistocene drumlins, Northern Ireland. Boreas; volume 12, pages 263–278. doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3885.1983.tb00321.x

DARDIS, G.F. – MCCABE, A.M., 1987 – Subglacial sheetwash and debris flow deposits in late-Pleistocene drumlins, Northern Ireland. Dans : Menzies, J. et Rose, J. (eds), Drumlin Symposium 1987, Balkema, Rotterdam, pages 225–240.

DARDIS, G.F. – MCCABE, A.M. – MITCHELL, W.I., 1984 – Characteristics and origins of lee‐side stratification sequences in late pleistocene drumlins, northern Ireland. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms; volume 9, pages 409–424. doi.org/10.1002/esp.3290090503

DAVIS, W.M., 1884 – ART. XLVIII–The distribution and origin of drumlins. American Journal of Science; volume 28, 407 pages.

DUNLOP, P. – CLARK, C.D. – HINDMARSH, R.C.A., 2008 – Bed ribbing instability explanation: Testing a numerical model of ribbed moraine formation arising from couple flow of ice and subglacial sediment. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface; volume 113, pages 1–15. doi.org/10.1029/2007JF000954

ELY, J.C. – CLARK, C.D. – SPAGNOLO, M. – HUGHES, A.L.C. – STOKES, C.R., 2018 – Using the size and position of drumlins to understand how they grow, interact and evolve. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms; volume 43, pages 1073‑1087. doi.org/10.1002/esp.4241

EMBLETON, C. – KING, C.A.M., 1975 – Glacial and periglacial geomorphology. 2ème edition, Edward Arnold, Londres, 573 pages.

EVANS, D.J.A., 2010 – Defending and testing hypotheses: A response to John Shaw’s paper ‘In defence of the meltwater (megaflood) hypothesis for the formation of subglacial bedform fields’. Journal of Quaternary Science; volume 25, pages 822‑823. doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1371

EVANS, D.J.A. – REA, B.R. – HIEMSTRA, J.F. – Ó COFAIGH, C., 2006 – A critical assessment of subglacial mega-floods: a case study of glacial sediments and landforms in south-central Alberta, Canada. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 25, pages 1638–1667. doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.12.007

EVANS, D.J.A. – ROBERTS, D.H. – Ó COFAIGH, C., 2015 – Drumlin sedimentology in a hard-bed, lowland setting, Connemara, western Ireland: Implications for subglacial bedform generation in areas of sparse till cover. Journal of Quaternary Science; volume 30, pages 537–557. doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2801

EYLES, N. – PUTKINEN, N. – SOOKHAN, S. – ARBELAEZ-MORENO, L., 2016 – Erosional origin of drumlins and megaridges. Sedimentary Geology; volume 338, pages 2–23. doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2016.01.006

FAIRCHILD, H.I., 1929 – New York Drumlins. Proceedings of the Rochester Academy of Science; volume 7, pages 1‑37.

FLINT, R.F., 1971 – Glacial and Quaternary geology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 892 pages.

FORSSTRÖM, L. – SHAW, J., 1990 – Comment and Reply on ‘Drumlins, subglacial meltwater floods, and ocean responses’. Geology; volume 18, pages 804–805. doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1990)018<0804:CARODS>2.3.CO;2

FOWLER, A.C., 2000 – An instability mechanism for drumlin formation. Geological Society Special Publication; volume 176, pages 307–319. doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2000.176.01.23

FOWLER, A.C., 2009 – Instability modelling of drumlin formation incorporating lee-side cavity growth. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences; volume 465, pages 2681–2702. doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2008.0490

FOWLER, A.C., 2010 – The instability theory of drumlin formation applied to Newtonian viscous ice of finite depth. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences; volume 466, pages 2673–2694. doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2010.0017

FOWLER, A.C., 2018 – The philosopher in the kitchen: the role of mathematical modelling in explaining drumlin formation. Geologiska Föreningens i Stockholm Förhandlingar; volume 140, pages 93–105. doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2018.1444671

FOWLER, A.C. – SPAGNOLO, M. – CLARK, C.D. – STOKES, C.R. – HUGHES, A.L.C. – DUNLOP, P., 2013 – On the size and shape of drumlins. GEM: International Journal on Geomathematics; volume 4, pages 155–165. doi.org/10.1007/s13137-013-0050-0

FRANCEK, M.A., 1991 – A spatial perspective on the New York drumlin field. Physical Geography; volume 12, pages 1–18. doi.org/10.1080/02723646.1991.10642415

HALL, J., 1815 – IV. On the Revolutions of the Earth’s Surface. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh; volume 7, pages 139–167. doi.org/10.1017/S0080456800019281

HART, J.K., 1994 – Till fabric associated with deformable beds. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms; volume 19, pages 15–32. doi.org/10.1002/esp.3290190103

HART, J.K., 1995 – Subglacial erosion, deposition and deformation associated with deformable beds. Progress in Physical Geography; volume 19, pages 173–191. doi.org/10.1177/030913339501900202

HART, J.K., 1997 – The relationship between drumlins and other forms of subglacial glaciotectonic deformation. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 16, pages 93–107. doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(96)00023-6

HART, J.K. – BOULTON, G.S., 1991 – The interrelation of glaciotectonic and glaciodepositional processes within the glacial environment. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 10, pages 335–350. doi.org/10.1016/0277-3791(91)90035-S

HART, J.K. – CLAYTON, A.I. – MARTINEZ, K. – ROBSON, B.A., 2018 – Erosional and depositional subglacial streamlining processes at Skálafellsjökull, Iceland: an analogue for a new bedform continuum model. Geologiska Föreningens i Stockholm Förhandlingar; volume 140, pages 153–169. doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2018.1477830

HERMANOWSKI, P. – PIOTROWSKI, J.A. – SZUMAN, I., 2019 – An erosional origin for drumlins of NW Poland. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms; volume 44, pages 2030–2050. doi.org/10.1002/esp.4630

HILLIER, J.K. – BENEDIKTSSON, Í.Ö. – DOWLING, T.P.F. – SCHOMACKER, A., 2018 – Production and preservation of the smallest drumlins. Geologiska Föreningens i Stockholm Förhandlingar; volume 140, pages 136–152. doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2018.1457714

HILLIER, J.K. – SMITH, M.J. – CLARK, C.D. – STOKES, C.R. – SPAGNOLO, M., 2013 – Subglacial bedforms reveal an exponential size-frequency distribution. Geomorphology; volume 190, pages 82–91. doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2013.02.017

HINDMARSH, R.C.A., 1996 – Sliding of till over bedrock: Scratching, polishing, comminution and kinematic-wave theory. Annals of Glaciology; volume 22, pages 41–47. doi.org/10.3189/1996AoG22-1-41-47

HINDMARSH, R.C.A., 1998 – Drumlinization and drumlin-forming instabilities: viscous till mechanisms. Journal of Glaciology; volume 44, pages 293–314. doi.org/10.3189/S002214300000263X

HINDMARSH, R.C.A., 1999 – Coupled ice-till dynamics and the seeding of drumlins and bedrock forms. Annals of Glaciology; volume 28, pages 221–230. doi.org/10.3189/172756499781821931

KEHEW, A.E. – LORD, M.L. – SHAW, J., 1990 – Comment and Reply on ‘Drumlins, subglacial meltwater floods, and ocean responses’. Geology; volume 18, pages 479–480. doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1990)018<0479:CARODS>2.3.CO;2

KILROE, J.R., 1888 – Directions of ice-flow in the north of Ireland, as determined by the observations of the geological survey. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London; volume 44, pages 827-833. doi.org/10.1144/GSL.JGS.1888.044.01-04.53

KINAHAN, G.H., 1874 – V.- Glacialoid or re-arranged glacial drift. Geological Magazine; volume 1, pages 168–174. doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800169316

KNIGHT, J., 2010 – Drumlins and the dynamics of the subglacial environment. Sedimentary Geology; volume 232, pages 91-97. doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2010.10.001

KOVANEN, D.J. – SLAYMAKER, O., 2004 – Glacial imprints of the Okanogan Lobe, southern margin of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Journal of Quaternary Science; volume 19, pages 547–565. doi.org/10.1002/jqs.855

KRÜGER, J. – THOMSEN, H.H., 1984 – Morphology, stratigraphy, and genesis of small drumlins in front of the glacier Myrdalsjokull, south Iceland. Journal of Glaciology; volume 30, pages 94–105. doi.org/10.3189/S0022143000008534

MCCABE, A.M. – DARDIS, G.F., 1989 – Sedimentology and depositional setting of Late Pleistocene drumlins, Galway Bay, western Ireland. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology; volume 59, pages 944–959. doi.org/10.1306/212F90C0-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D

MENZIES, J., 1979 – A review of the literature on the formation and location of drumlins. Earth Science Reviews; volume 14, pages 315-359. doi.org/10.1016/0012-8252(79)90093-X

MENZIES, J., 1984 – Drumlins: a bibliography. Geo Books, Norwich; Geo Abstracts Bibliography 15. 117 pages.

MENZIES, J., 1987 – Towards a general hypothesis on the formation of drumlins. Dans : Menzies, J. et Rose, J. (eds), Drumlin Symposium 1987, Balkema, Rotterdam, pages 9–24.

MENZIES, J. – BRAND, U., 2007 – The internal sediment architecture of a drumlin, Port Byron, New York State, USA. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 26, pages 322–335. doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.07.003

MITCHELL, W.A. – RILEY, J.M., 2006 – Drumlin map of the Western Pennines and southern Vale of Eden, Northern England, UK. Journal of Maps; volume 2, pages 10–16. doi.org/10.4113/jom.2006.45

MITCHELL, W.A., 1994 – Drumlins in ice sheet reconstructions, with reference to the western Pennines, northern England. Sedimentary Geology; volume 91, pages 313‑331. doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(94)90137-6

NEWMAN, W.A. – MICKELSON, D.M., 1994 – Genesis of Boston Harbor drumlins, Massachusetts. Sedimentary Geology; volume 91, pages 333–343. doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(94)90138-4

NSIDC, 2020 – Glacier Landforms: Drumlins. National Snow and Ice Data Center; page web visitée le 2 octobre 2020. Source

Ó COFAIGH, C. – DOWDESWELL, J.A. – KING, E.C. – ANDERSON, J.B. – CLARK, C.D. – EVANS, D.J.A. – EVANS, J. – HINDMARSH, R.C.A. – LARTER, R.D. – STOKES, C.R., 2010 – Comment on Shaw J., Pugin, A. and Young, R. (2008): ‘A meltwater origin for Antarctic shelf bedforms with special attention to megalineations’, Geomorphology; volume 102, pages 364-375. doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.09.036

PATTERSON, C.J. – HOOKE, R.L.B., 1995 – Physical environment of drumlin formation. Journal of Glaciology; volume 41, pages 30–38. doi.org/10.3189/S0022143000017731

RAINS, B. – SHAW, J. – SKOYE, R. – SJOGREN, D. – KVILL, D., 1993 – Late Wisconsin subglacial megaflood paths in Alberta. Geology; volume 21, pages 323‑326. doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0323:LWSMPI>2.3.CO;2

ROSE, J., 1987 – Drumlins as part of a glacier bedform continuum. Dans : Menzies, J. et Rose, J. (eds), Drumlin Symposium 1987, Balkema, Rotterdam, pages 103–116.

SCHOMACKER, A. – JOHNSON, M.D. – MÖLLER, P., 2018 – Drumlin formation: a mystery or not? Geologiska Föreningens i Stockholm Förhandlingar; volume 140, pages 91–92. doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2018.1485326

SCHOOF, C., 2007a – Cavitation on deformable glacier beds. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics; volume 67, pages 1633–1653. doi.org/10.1137/050646470

SCHOOF, C., 2007b – Pressure-dependent viscosity and interfacial instability in coupled ice-sediment flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics; volume 570, pages 227–252. doi.org/10.1017/S0022112006002874

SHARPE, D.R. – CLARKE, G.K.C. – LEVERINGTON, D.W. – TELLER, J.T. – DYKE, A.S. – MARSHALL, S.J., 2005 – Comments on: ‘Paleohydraulics of the last outburst flood from glacial Lake Agassiz and the 8200 BP cold event’. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 24, pages 1529–1532. doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.01.004

SHAW, J., 1983 – Drumlin formation related to inverted melt-water erosional marks. Journal of Glaciology; volume 29, pages 461–479. doi.org/10.3189/S0022143000030367

SHAW, J., 1989 – Drumlins, subglacial meltwater floods, and ocean responses. Geology; volume 17, pages 853–856. doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1989)017<0853:DSMFAO>2.3.CO;2

SHAW, J., 1996 – A meltwater model for Laurentide subglacial landscapes. Dans: McCann, S.B., Ford, D.C. (eds), Geomorphology Sans Frontieres. Wiley, Chichester, pages 181-236.

SHAW, J., 2002 – The meltwater hypothesis for subglacial bedforms. Quaternary International; volume 90, pages 5–22. doi.org/10.1016/S1040-6182(01)00089-1

SHAW, J., 2007 – A Glimpse at Meltwater Effects Associated with Continental Ice Sheets. Dans : Glacier Science and Environmental Change, John Wiley & Sons., pages 25‑32. doi.org/10.1002/9780470750636.ch4

SHAW, J., 2010a – In defence of the meltwater (megaflood) hypothesis for the formation of subglacial bedform fields. Journal of Quaternary Science; volume 25, pages 249–260. doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1264

SHAW, J., 2010b – Reply: Defending and testing hypotheses: A response to John Shaw’s paper ‘In defence of the meltwater (megaflood) hypothesis for the formation of subglacial bedform fields’. Journal of Quaternary Science; volume 25, pages 824‑825. doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1374

SHAW, J. – KVILL, D. – RAINS, B., 1989 – Drumlins and catastrophic subglacial floods. Sedimentary Geology; volume 62, pages 177–202. doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(89)90114-0

SHAW, J. – YOUNG, R.R., 2010 – Reply to comment by Ó Cofaigh, Dowdeswell, King, Anderson, Clark, DJA Evans, J. Evans, Hindmarsh, Lardner and Stokes « Comments on Shaw, J., Pugin, A., Young, R., (2009): A meltwater origin for Antarctic Shelf bedforms with special attention to megalineations. Geomorphology; volume 117, pages 199–201. doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.12.008

SHOEMAKER, E.M., 1992 – Water sheet outburst floods from the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences; volume 29, pages 1250–1264. doi.org/10.1139/e92-100

SMALLEY, I.J. – UNWIN, D.J., 1968 – The formation and shape of drumlins and their distribution and orientation in drumlin fields. Journal of Glaciology; volume 7, pages 377–390. doi.org/10.3189/S0022143000020591

SMALLEY, I.J. – WARBURTON, J., 1994 – The shape of drumlins, their distribution in drumlin fields, and the nature of the sub-ice shaping forces. Sedimentary Geology; volume 91, pages 241–252. doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(94)90132-5

SPAGNOLO, M. – CLARK, C.D. – HUGHES, A.L.C., 2012 – Drumlin relief. Geomorphology; volume 153–154, pages 179–191. doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.02.023

STANFORD, S.D. – MICKELSON, D.M., 1985 – Till Fabric and Deformational Structures in Drumlins Near Waukesha, Wisconsin, U.S.A. Journal of Glaciology; volume 31, pages 220–228. doi.org/10.3189/S0022143000006535

STOKES, C.R. – CLARK, C.D., 1999 – Geomorphological criteria for identifying Pleistocene ice streams. Annals of Glaciology; volume 28, pages 67–74. doi.org/10.3189/172756499781821625

STOKES, C.R. – CLARK, C.D., 2002 – Are long subglacial bedforms indicative of fast ice flow? Boreas; volume 31, pages 239–249. doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3885.2002.tb01070.x

STOKES, C.R. – FOWLER, A.C. – CLARK, C.D. – HINDMARSH, R.C.A. – SPAGNOLO, M., 2013 – The instability theory of drumlin formation and its explanation of their varied composition and internal structure. Quaternary Science Reviews; volume 62, pages 77–96. doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.11.011

STOKES, C.R. – SPAGNOLO, M. – CLARK, C.D., 2011 – The composition and internal structure of drumlins: Complexity, commonality, and implications for a unifying theory of their formation. Earth-Science Reviews; volume 107, pages 398‑422. doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.05.001

TARR, R.S., 1894 – The origin of drumlins. The American Geologist; volume 13, pages 393-407.

UPHAM, W., 1889 – The structure of drumlins. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural Society; volume 24, pages 228–242.

Collaborateurs

|

Première publication |

Simon Hébert, géo. stag., M.Sc. Simon.Hébert@mern.gouv.qc.ca (rédaction) Olivier Lamarche, géo., M. Sc. olivier.lamarche@mern.gouv.qc.ca (lecture critique); François Leclerc, géo., Ph.D. (conformité du gabarit et du contenu); Simon Auclair, géo., M.Sc. (révision linguistique); Céline Dupuis, géo., Ph.D. (version anglaise). |

21 janvier 2021